1976

In a Southall ravaged by fascist attacks, the unassuming Ramgharia Sabha Southall sits nestled on Oswald Street, amid flickering kaleidoscopic images of British-Asian duality. ‘Little India’, they call it, but the cheerful signage on facades hints to trouble brewing beneath; migrant communities are all too aware that this is not truly home—yet.

And though the streets are rife with the banners and reverberations of the Southall Asian Youth Movement, within the walls of Ramgarhia Hall, a different type of insurrection is taking place—peaceful, yet not acquiescing. Meaningful. Mosaic. Musical.

Stark black curtains shroud the slightly mildewed hall and jackets are strewn across the patched carpet. The walls sag under the weight of makeshift mattresses and wooden beams—likely remnants of another extracurricular activity conducted in the multi-purpose hall—but the permeating atmosphere is anything but oppressive.

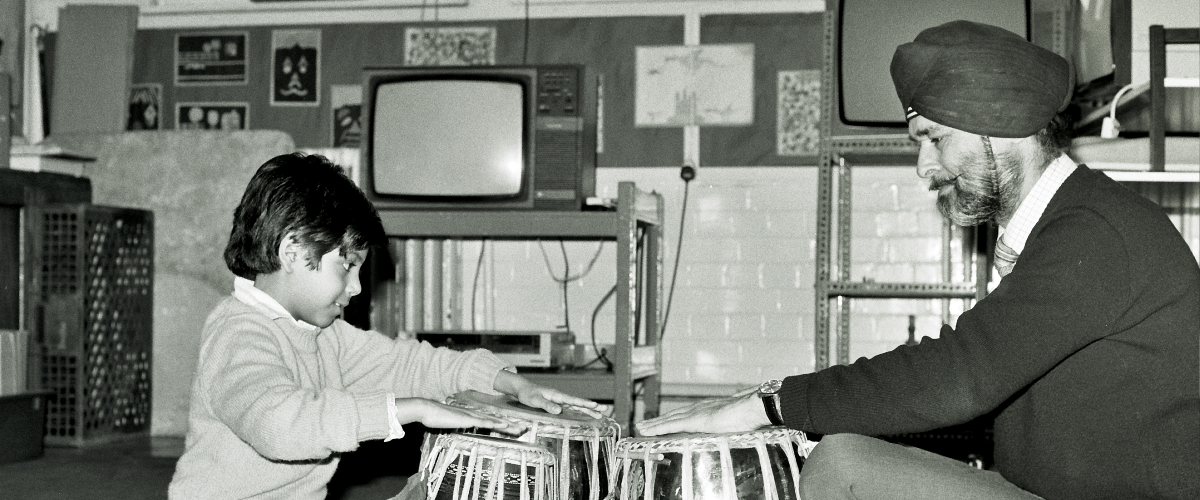

With a motley of young children and young-at-heart adults, the air buzzes with nearly 50 pairs of hands poised atop their instruments. Each student, with rapt attention, either recalls the lesson, reads from meticulous notations or listens, mesmerised, to direct assistance. Some sit on the sidelines and bask in the richness of the music, unknowingly learning through osmosis even as they wait. Those next to him hang on his every word and watch how his fingers are placed as they produce divine music.

100 hands. 100 eyes and ears. 50 twin tablas. One teacher.

He teaches not just music, but a way of life. And with his musical passion, he does not lead a political mutiny, but hosts a homecoming of sorts for his people’s heritage. Within these walls, and with his tabla students, he is making history. It is the beginning of a legacy that will leave indelible marks on hundreds if not thousands of the world’s finest Indian classical musicians and spawn a veritable movement.

Who is this man?

2016

A purpose-built stage is enshrined with sanctity as the artistic director walks, barefoot, to light the jot (an ornately embellished brass candle traditionally used in Indian spiritual practices) to bless the auspicious occasion. The temperature is purposefully controlled at a balmy 21 to 22°C for an authentic Indian feel, and the sedulously erected sandstone backdrop—stately testament to the Mughal courts and ancient temples of centuries-past—is bathed in the warmest light, softened by slowly ascending haze. With all this mystique conjuring up the grandeur of the East, it seems more Ganges than Thames, and one would hardly guess it’s in the heart of London.

Not patched with faded carpets or makeshift walls, the 2,700 seater Royal Festival Hall is state-of-the-art, decked out with one of the most advanced PA systems and over 2 crore INR worth of filming equipment to capture the elaborate affair.

And yet, an aura of old-world subcontinental exoticism is conjured up. Instead of building a Little India, it seems the essence of Indian heritage has been distilled and infused, amplified by the aura of reverence and anticipation hanging palpably amidst the spectators.

Here, on the same stage that is home to the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Philharmonia Orchestra and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, today, in the realm of Indian classical music, history is being made. For the now second and third generation migrants who constitute roughly half of the audience (the other half is non-South Asian), finally, it feels like home.

His head bowed in deference, Sandeep Virdee, the artistic director—awarded an OBE by Her Majesty for his services to the promotion of Indian Musical Heritage in the UK—acknowledges the shoulders of giants who have contributed to today’s success, and pays homage to his father who has spurred this phenomenal success—all without being the largest, most well-known or the most prolific musician. A man who, by virtue of his commitment to the Sikh principle of Wand kay Shako (or giving generously) inspired change and spurred equal recognition. Who felt that breaking the stifling system of oppression and snobbery in Indian classical music was the only way to preserve the artform and provide a platform to deserving artists.

He is synonymous with the Darbar Festival—the single light guiding it, if you will—despite the festival being posthumously conceived and not being eponymously named. He is the man who inspired unprecedented success—within a span of 16 years, Darbar has grown from a tribute conceptualised by his contemporaries to pay homage to his life and grown exponentially to become a platform that has hosted over 400 artists.

Who was this man?

|

The void At 67 years old and in the prime of his health, Bhai Gurmit Singh Ji Virdee (hereafter referred to as Gurmit Ji) stood at a staggering 6 ft 2inches, towering in the lives of his many loved ones not just because of his physical stature and charismatic personality, but his irresistible joie de vivre. “Like the Kennedy of the Sikh world”, sources say, he was ‘strikingly good-looking’. Imagery used to describe his persona repeatedly features phrases such as ‘larger than life’, ‘magnetic’, ‘exuberant’ and ‘animated.’ At times, his presence seemed to defy mortality itself. On Friday, 1, March 2005, Gurmit Ji went to see his daughter, Ameeta, and son-in-law, Sukh Dhanjal (his former tabla student turned tabla teacher himself) in Hayes for dinner, en route to spend the weekend with his younger son in High Wycombe to purchase a car for his wife. At his daughter’s house, the teacher in him couldn’t help but sit in while his son-in-law taught a tabla student. Almost as if he had a premonition, Dhanjal recalls Gurmit Ji saying, “You should ask your students to start recording my lessons. I don’t know how long I’m going to be here.” At the time, even entertaining the thought seemed absurd. “What are you talking about?” nudged Dhanjal playfully, “Don’t be silly.” Gurmit Ji appeared, to everyone around him, to have at least a few more decades in him. But that impromptu tabla lesson would be his last. On March 3rd, less than 48 hours after that fateful tabla lesson, Gurmit Ji passed away, leaving what has been described by dozens of his dearest as ‘a void’. Among thousands of people who flocked to his funeral to pay his respects? The car salesman from his last purchase—an Asian car dealer who interacted with him for all but a few minutes, but was so deeply drawn by Gurmit Ji’s aura that he drove two hours to pay his respects. “If that was the type of impact his presence had on an acquaintance, imagine how profoundly he touched the lives of those he knew,” asks his younger son, Harmeet. It was this pull, this je ne sais quoi, that culminated in this master-musician, dedicated tabla teacher, lover of art and all things beautiful, deeply devoted spiritual kirtania, emissary for Indian classical music and luminary for Darbar. His son, Sandeep, vividly recalls one moment from the funeral, which, he says, wasn’t a sullen affair at all. It was a celebration of his life, of the way he committed it to Wand kay Shako, and the many ways in which his impact lives on today. “We were bringing the body out of the Gurudwara [Guru Nanak Nishkam Sewak Jatha] one last time after paying the last respects. Being at the front, I couldn’t see then that all his sewadars [including tabla students] had climbed on the rooftop and were showering thousands of flowers. I looked up and all I remember is seeing clear blue sky splayed with all this vibrant color...and I thought to myself, ‘This, right here, is grace.’” Who was this man, and what was the illustrious life leading up to this moment? Parched Land Born in the small village of Malri in the Indian province of Punjab on April 13, 1937 (A significant date, as it is Vaisakhi, the annual day Sikhs globally celebrate the birth of the Khalsa by Guru Gobind Singh Ji in 1699), Gurmit Ji moved to Kenya with his parents at a very young age. Though he trained in the family’s artisan craft of joining wooden furniture, he harboured dreams of studying medicine, and ultimately returned to India to pursue his higher education. But during his time in Kenya, another seed had already been planted: his unfettered love for playing the tabla. In 1954, Gurmit Ji, then 17 years old, had started learning the violin from Acharya Ji, who was accompanying Ragi Udam Singh Devsi, a student of Ustad Fiyaz Khan Sahib. In 1957, at the age of 19, he embarked on what would become a lifelong pursuit of excellence in playing the tabla. His first teacher, Mohinder Singh Bharj Ji, fueled his burgeoning interest and helped establish a solid foundation, and ultimately introduced Gurmit Ji to Ustad Bahadur Singh Ji in 1960.

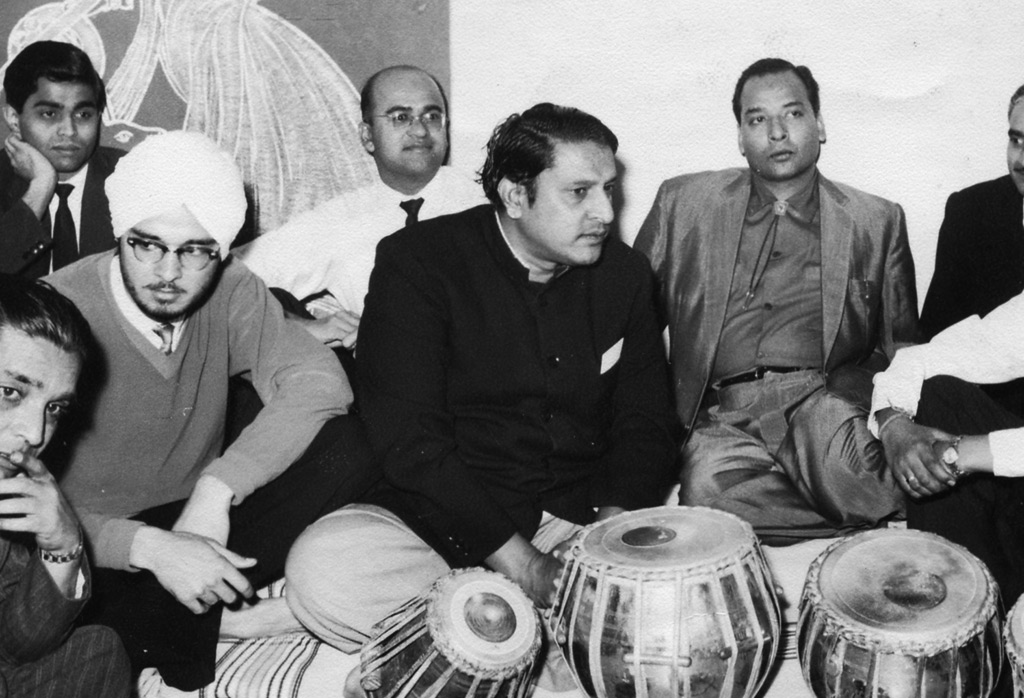

In India, his education trajectory, which had already taken a turn with a degree in Biology instead of medicine, morphed into his pursuit of playing, learning and teaching the tabla. Traveling deep into the heart of Punjab, Gurmit Ji approached Ustad Bahadur Singh Ji (1902-1967), a disciple of Ustad Meeran Baksh with lineage tracing back to the Kasur Ang of the Punjab Gharana, one of many offshoots within the sprawling musical ‘house’. This act of defiance—because studying music was a less socially acceptable construct at the time—would be one of multiple acts of surrender in his musical and mystical journey. In a land he had not been in for decades, reverberating with unfamiliar dialects and begrudgingly hosted by an almost alien landscape, he was guided by the singularity of his passion to relinquish all control and surrender at his Ustad’s doorstep. He came bearing fruit, as a goodwill gesture part of the guru-shishya etiquette protocol. In keeping with the tradition of the parampara, he proceeded to spend that first weekend sweeping the maestro’s house, fetching groceries and trailing his every move, desperate for one wayward nugget of wisdom to be cast his way. But the weekend came and went without a single lesson. It was only at the train platform, when a disenchanted Gumit Ji slumped defeatedly towards his return, that a fellow student, Ranjit Singh, raced after him and fervently—feverishly, almost—whispered a lone tabla bol to him on the station platform. It was a bol (spoken language of tabla) Gurmit Ji cherished and wrote down. Following that fateful first visit, Gurmit Ji continued to visit India to further both his musical and conventional education. In total, he made four to five trips—all under the guise of his primary degree, which he was undoubtedly excellently proficient at, but learning the tabla was his loftier, more elusive goal. In his college—the same as the famed ghazal singer Jagjeet Singh (with whom he cultivated a relationship and eventually toured with multiple times)—Gurmit Ji actively sought opportunities to play with, learn from and perform alongside as many individuals as possible, gingerly adding to the threads on his loom of knowledge. One of those individuals was Ustad Badlev Singh Narang Ji, and subsequent visits to Ustad Bahadur Singh also proved more fruitful, paving the way for three to four years of sustained learning and culminating in a relationship the duo encapsulated in a local photography studio for a keepsake. Surrounded by avid students of the tabla, Gurmit Ji and his peers also learned organically from each other, triggering opportunities to perform and hone his artform further. Surrender to lifelong learning And so, he trained in the Punjab gharana, gleaning information from a multitude of sources and guided by an almost intuitive understanding of the artform. Although Gurmit Ji had already attained proficiency to the level that he played tabla solos at the Kenya Broadcasting Station, he was the epitome of a lifelong learner, seeking to make even more dramatic improvements in his craft. In 1968, Pandit Samta Prasad toured East Africa whilst accompanying Ustad Vilayat Khan, and initiated a ganda bhandan relationship with Gurmit Ji, wherein a sacred thread is ceremoniously tied on the disciple’s wrist by the guru to consecrate a lifelong bond between student and teacher.

The ensuing ceremony, redolent with intricacies passed down generations, was blessed with all the sanctity of Sanskrit recitation, a lump of jaggery placed in the mouth and subsequent gifts offered by the disciple. In Gurmit Ji’s case, this time, the gift was not fruit or something of nominal value. Despite being a newlywed at the time, his gift to his guru was his wedding ring and watch—not because he valued his marriage any less, but because the knowledge he set out to attain represented, “...an equal treasure to him. 1” And the deep seated desire to manifest continuous learning and refinement in any way possible continued to be a predominant motif in Gurmit Ji’s life much into his later years as well. Even as late as 1982, he learned from Pandit Anil Palit, who had come from India with Pandit Devabrata (Debu) Chaudhuri, Gurmit Ji seized the opportunity to embrace a new style. Because to him, rigidly conforming to one school or musical gharana was less important than imbibing whatever he thought sounded beautiful to the ear. He struck a beautiful wager with Pandil Anil Palit: “You teach me Banaras, and I’ll teach you Punjab.” At another point in time, he also endeavoured earnestly to train in the Farooqabad gharana style. Just as the word Sikh means student, Gurmit Ji was a student and learner at heart, and truly personified the idea of submitting to the pursuit of knowledge. To learn, one has to submit, explains Sandeep, and classical tradition extols the emptiness of the vessel (i.e. the student) in order to be a receptive recipient of the knowledge poured forth by the teacher. The Mango Tree But Gurmit Ji vanquished that system. Though his own initiation into the world of Indian classical music was riddled with laboured staccato spurts and weighed down by ritualistic expectation, the manner in which he continued the tradition was nothing short of revolutionary. Indian classical music, despite centuries of rich history—or perhaps because of it—is still tainted by ego, superiority and money, says Sandeep. “Dad [Gurmit Ji] had several very tough episodes related to teaching. But he made sure he never perpetuated that cycle. Instead, he made sure he became a conduit and shared his knowledge freely and openly for the next 30 years.” The sentiment is affirmed by his multitude of students, who liken Gurmit Ji’s open sharing of knowledge to the belief that the more mangoes are picked from the archetypal Indian mango tree, the higher the harvest is in the next season. Spurred by the difficulties he faced, Gurmit Ji was determined to teach his students in such a transparent and easily digestible manner that they wouldn’t even realise how effortlessly they were learning. But Gurmit Ji was a teacher long before he started teaching tabla. In Kenya, during the early years of his marriage, he taught Biology and Chemistry at Chania High School. Shaminder, Gurmit Ji’s older daughter, recalls her father’s museum-esque high school classroom, lined with shelves proudly displaying skeletons, embryos, fossils and plant life specimens—each immaculately labeled in his Victorian-style, sprawling handwriting. “The students were absolutely besotted by his teaching methodology,” she explains, “They’d sit, entranced by his lessons, until 5 pm. And he’d welcome them to come back later at 7 pm if they were still interested. And they all did. Every. Single. One.” In many ways, Gurmit Ji sparked a love for learning that extended far beyond one curriculum or branch of science alone—all during an epoch when application and project based learning weren’t yet commonplace, Gurmit Ji imbibed these fundamental principles and bestowed them on his students. “Outside the lab, he’d built a big enclosure with rabbits and tortoises,” explains Shaminder, “Once, there was an injured dik-dik [a dwarf antelope] that dad and the students nursed back to health together.” The birth of a movement When the practical rigour of science met with the creativity of music, an intriguing and riveting combination was born. Gurmit Ji started tutoring students, initially at Ramgharia Hall every Friday in Southall, and then every Wednesday at home. From 1976 to 1982, he taught in London. After the family moved to Liecester, he carried on teaching every Wednesday at home, and at several different places—including at the Midlands Arts Center in Birmingham and multiple centers and gurudwaras at Coventry, Birmingham, Nottingham, Leicester and London. But this burgeoning institutionalised popularity within the UK for a classical Indian instrument, the tabla, does not reflect the innumerable ad-hoc sit downs, called baithaks (musical sit downs), that Gurmit Ji organised. To him, sharing his passion for the tabla was an activity to engage in anytime, anywhere, regardless of whether it was at the langar hall (a communal free kitchen for Sikhs), the backseat of a car or a parking lot. His uncontainable love to share all that he knew was bursting at the seams. And yet, he disseminated knowledge in the most methodical manner. “Tabla flowed from his soul, but when he passed it on, he was able to dissect the complexities because his personality included creativity as well as scientific analytical skills,” explains his student .

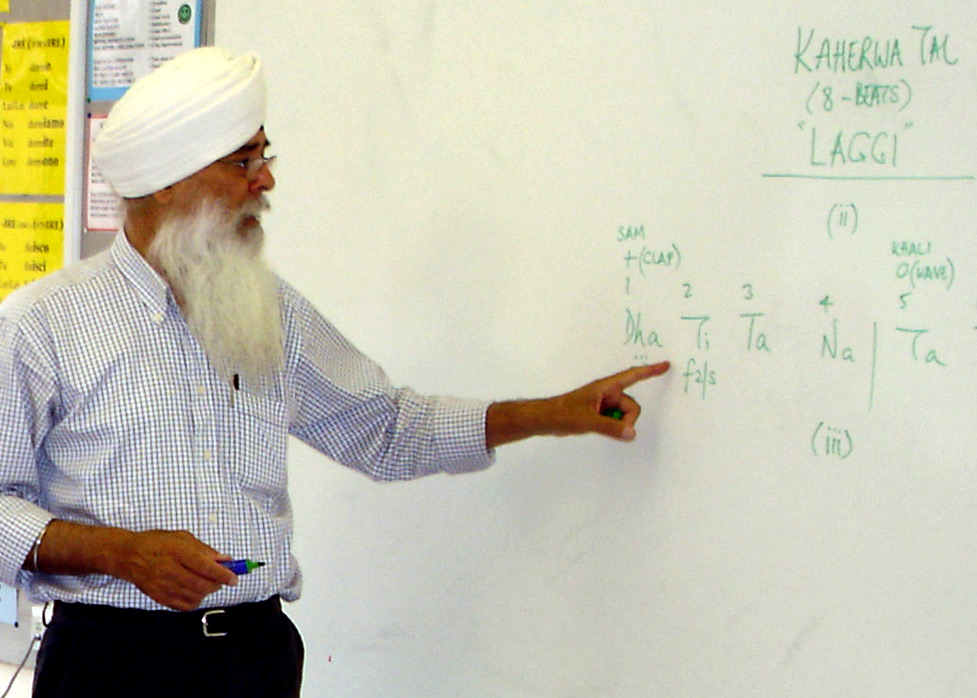

Gurmit Ji’s notation system is regaled by countless students as being meticulous and unprecedented in the level of detail it afforded. With his students’ name and his own signature, students today treasure the reverentially presented lessons as birthday or special occasion cards. A far cry from the hastily whispered bol he clung to on that fateful train station platform, Gurmit Ji pioneered a customised system of penning down the ponderous spoken language of tabla. From the A-4 sized sheets of blank printer paper—where somehow no lines ever went awry—to the beautiful handwriting and specific symbols signifying the right or left hand as well as the finger to be used, or the standard name and date in the corner (for the lessons were lovingly customised to cater to the needs of each student), his notations were a work of art in and of themselves. “Even the manner in which he recited parans [compositions displaying the virtuosity of the tabla player] would come up silky smooth and beautiful. His recitation was like a language on it’s own, because he commanded musicality in everything,” says a student . Ever the perfectionist, multiple students vividly recall his biro pen and Tipp-Ex correction fluid, which he’d whip out to correct even the slightest error. Epitomising excellence himself, he expected it of his students. More importantly, he worked tirelessly to help them achieve it. This high degree of finesse extended from the placement of his students’ hands—one student recalls having her finger painted red to help her remember it needed to stay down , while another re-learnt appropriate hand positioning because his previous tabla teacher had been left-handed, leaving his dominant right hand well-positioned, but his left hand, ‘a mess’. Gurmit Ji assigned elaborate finger exercises, made modifications to each students’ lessons to help them scaffold learning and reap bigger dividends through hyper-planned modules, and upheld an uncompromised focus on quality and respect for the art form. His classes, while homely and charming and often extending well beyond the stipulated duration of the session, were also perfectly orderly, “We’d never go in there with a funny face or something,” recalls a student . But the untainted love with which he did it all made each lesson feel like a treasure. “It’s the stickability,” said his student , “As if Ustad ji was handing it all to us, recontextualised for our diaspora because the books had hitherto been in Hindi or Punjabi. The sum was there, the details were there...he was Google for that day.” What he gave to his students far exceeded the sum of its parts, and his work stoked an inextinguishable fire. Decades later, another one of his students shares, “Hand on my heart, there was no system like Gurmit uncle’s...I feel I’m still just scratching the surface and one life isn’t enough. I wish there was another life for me to come back and do more riyaaz.” He made a place in their hearts and consciousness—and even on their mantels. “There is not a single day that’s gone by that I don’t think of my guru ji,” says his student , sitting under a framed portrait of his teacher. Because like the self-effacing mango tree, in giving, Gurmit Ji received—not accolades or monetary gain (his classes were never adjusted for inflation, nor did he maintain an elaborate register to process payments, and the reasonable charge was more than offset by homemade chai and aloo parathas for students to indulge in)—but grace.

From 1982 to 2004, Gurmit Ji had what his younger son Harmeet describes as his dream job, teaching tabla as part of Leicester-Shire Schools of Music services as a peripatetic teacher, serving over 50 schools across Leicester. The project, aimed towards providing more equal representation in the curriculum for the diverse ethnic population and to bring authentic Indian Classical Music in its most thrilling form to the UK, was “...incredible, fascinating and groundbreaking,” says Harmeet. With Gurmit Ji teaching tabla, Ustad Dharambir Singh Dhadhyalla, MBE, on the sitar, Ramik Varu teaching vocals and Kumar Shashwat teaching kathak dance, the formidable foursome painted the primary and secondary schools with their vibrant heritage. Most Fridays, they would give presentations or demos during assembly to introduce the instruments and artforms to the student body, captivating them with their hypnotic performance. With this project, Gurmit Ji was able to cast a much wider net than before, and teach students from diverse backgrounds, introducing them to this world of rhythm and mathematics in action. With time, his systematic approach served as inspiration for the cyclical patterns in Indian classical music to be featured as part of the Key Stage 2 National Curriculum, UK—and his own student was approached to devise a syllabus to help teachers disseminate these fundamentals.

On Saturdays, about 50 students with the most developmental potential congregated to hone their craft in a class the four teachers conducted at community college. “It was this hotpot of talent,” says Harmeet, referencing the many students who went on to have prolific careers in Indian classical music from this grassroots initiative, including, but not limited to Roopa Panesar and Harmeet himself. “We kept each other going. In the first half [of the day], we’d focus on our respective artforms. But after lunch, we’d work together.” Harmeet, who plays the sitar, recalls watching his father during the lunch breaks and feeling borne by this power and passion greater than himself. “It was the guru shishya without the ghanda bandhan,” summed up Harmeet. Gurmit Ji also ensured students were exposed to a wide array of musical styles, often inviting other eminent tabla players and artists to his classes, or, more commonly, his summer camp—a move virtually unheard of in the tightly-guarded disciple system. “One would think, if I give too much, the students will surpass the master. But Gurmit Ji? He was completely the opposite,” said a student. And such benevolent sharing—of knowledge, influence, musical inspiration and styles—led to a colourful tapestry and thrilling environment. “It’s amazing, actually, that Indian classical music is so vibrant outside of India,” says Panesar, who was one of very few females playing the sitar at the time. The warmth and ‘child-like energy’ she fondly remembers Gurmit Ji (whom she called Uncle Ji) exemplifying has stayed with her throughout her journey, “The musicians of our generation...we’re not just teaching. We’re committed to promoting and giving a platform to the students,” she says of this virtuous cycle to carry forth the legacy left behind. At its strongest, the Saturday Ensemble practice sessions saw five to 15 concerts throughout the year, with well-attended showcase concerts in May and November. The students even performed at the BBC Proms. And the constant focus on practise and performing—on touring, even (including to Berlin and LA), lent impetus and made for constant motivation and a beautifully nurturing environment. But of primary concern to Gurmit Ji was where his tabla students were going, and how conducive the Indian classical music landscape was for their arrival. Not unlike a farmer tilling his field to prepare for them to settle in and harvest, Gurmit Ji and his family put in the legwork to ensure tabla students would have a receptive welcome and initiation into the field and, perhaps more importantly—tangible role models to aspire to in a professional context. Beyond Baithaks: Taal – Rhythms of India

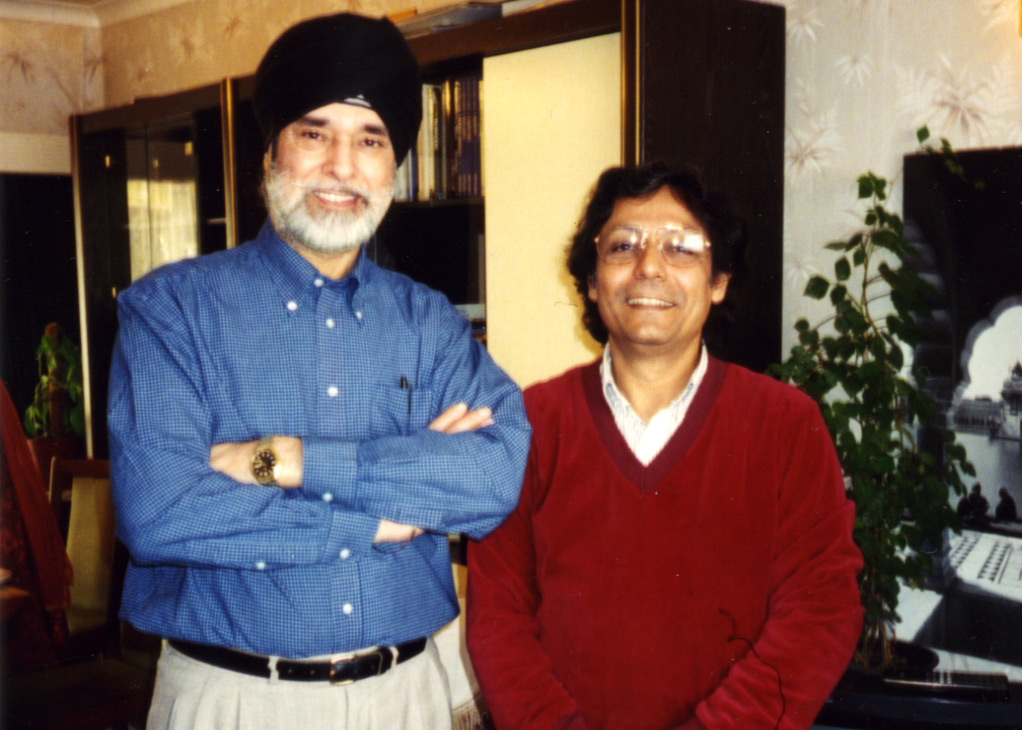

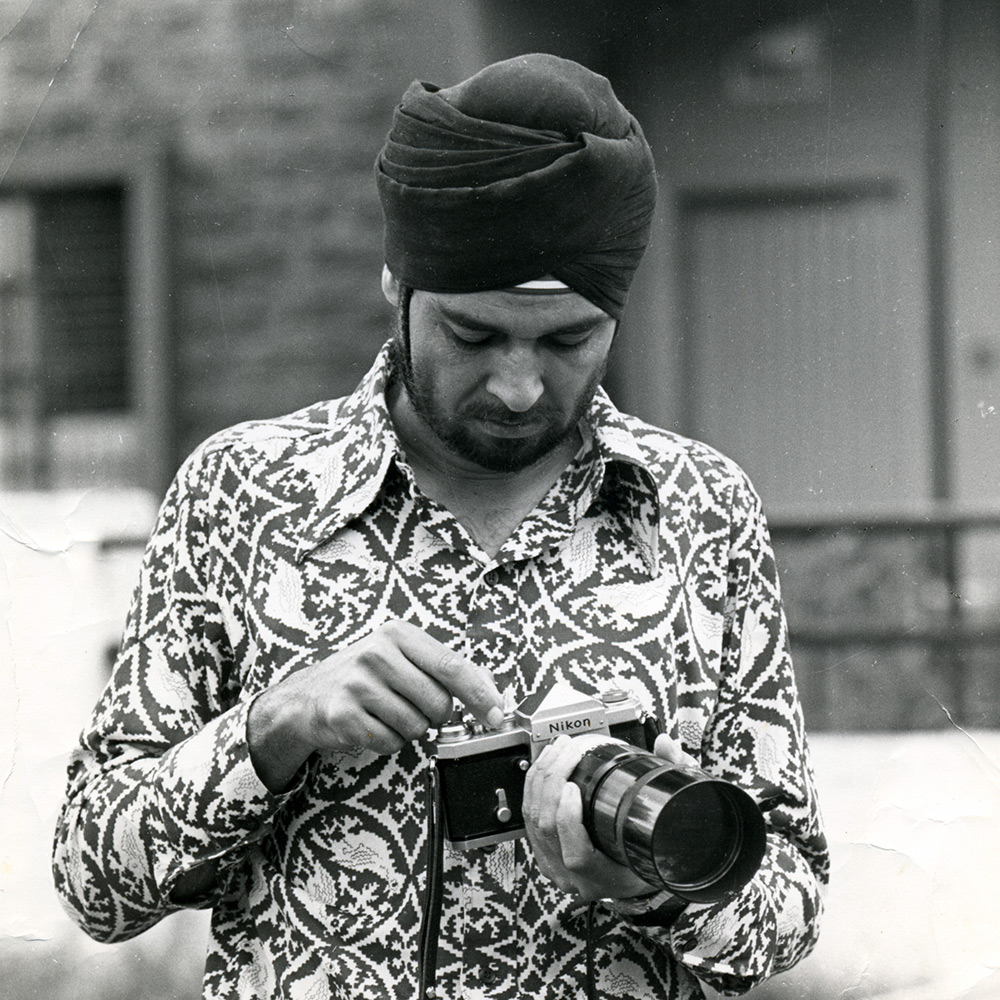

The initial reaction to these famed artists being told there would be a concert exclusively showcasing tabla solos? “They thought we were mad,” laughs Sandeep in retrospect. But it’s the people who think they’re crazy enough to change the world that ultimately end up doing so, and during the decade of Taal’s operations (from 1986 to 1996), the father and son organised 17-18 concerts. Within the fabric of the UK diaspora and quite possibly all around the world, this was a pivotal paradigm shift allowing tabla players such as Gurmit Ji’s students to see a vision of themselves on center-stage, with the possibility of getting the due recognition they deserved. “The tabla player was always considered the accompanying artist,” explains Sandeep, “Bringing them on par was a groundbreaking advancement—not just for tabla soloists, but for accompanying artists in general.” To this day, Darbar fights the status quo of paying nominal fee to accompanying artists, or differentiating between the vocalist and accompanying musicians, taking care to extend the same respect, fee and hospitality services to everyone. “A good concert can only happen if you have a strong tabla player and strong accompanying musicians,” says Sandeep, “You’re a team; you're all together. How you interact is how you perform...that’s what makes you great.” Alongside Taal, Gurmit Ji also lent his influence and time to his (by then) son-in-law Harkirat’s organisation, Chakardar. His oldest senior student, Harkirat had always possessed a similar fire as Gurmit Ji, and gone on to establish an organisation of his own to promote the tabla in all its glory. By teaching in the summer school programme at Chakardar, Gurmit Ji was leaving another lasting imprint—giving of himself selflessly to crystallise his vision for tabla going forward. Working with the likes of famed tabla players such as Pandit Shankar Ghosh, Pandit Sharda Sahai, Ustad Zakir Hussain, Pandit Anindo Chatterjee, Pandit Swapan Chaudhuri and Pandit Kumar Bose (both for Taal and Chakardar), Gurmit Ji established strong friendships in the professional tabla fraternity—ties that lasted, even after he was gone. Especially after he was gone. Upon hearing of Gurmit Ji’s death, it was these critically renowned tabla players (Anindo Ji, Kumar Ji and Swapan Ji) who conceived the idea to come and pay tribute to him, a development that forms another link in the chain of events behind the history of Darbar. He had set up a legacy and shifted mindsets in meaningful, sustainable ways. And the world of music would never be the same again. Beautifully blurred boundaries Still, despite Gurmit Ji’s pervasive institutionalised influence, it was the way he approached tabla—and, by extension, life itself—that most remember. “He helped us harness that passion...that understanding that it’s not just an instrument but a way of life,” says Rohit Mistry, one of the few students who called him Sir. Growing up, Ameeta, his younger daughter, recalls tabla permeating her consciousness—the soundtrack to her life and childhood. “It was just always resonating within our home and our heartbeats. If not students, then he’d be talking about music, listening to music or doing his riyaaz in the evenings,” she shares. But her father’s love for all things beautiful bled into art, photography and nature as well. “He was just in awe of everything god-given and beautiful,” says Ameeta. Shopkeepers at Sona Rupa [a festive ethnic dress shop in Leicester run by Chandu Matani, a successful businessman, bhajan singer and founder of Shruti Arts, an organisation that delivered regular Indian classical music concerts in Leicester] jostled to show off their wares because they knew he’d appreciate exquisite craftsmanship on regal sarees; family members entrusted him with the task of bringing back heavily embellished bridal lehngas from India; boutique-owners humoured his desire to sketch upscale embroidery designs for his wife to replicate at home, and his refined taste in jewelry was admired by all. And with photography, she shares, he transformed what was overlooked by many into meaningful art. “He simply didn’t have time for the mediocrity of life,” explains Shaminder, alluding to her father’s desire to attain excellence and mastery over whatever he did. Though many remember his talent as a musician, his talent in photography and art was equally commendable. Gurmit Ji chose to surround himself with the sublime aesthetic value of the seemingly trivial everyday. Capturing the essence “He’d be out photographing a leaf stuck in a gate, or flowers blooming from the pavement,” recalls Shaminder. For Ameeta and Harmeet, the strong scent of developer in the house is one of their most vivid olfactory memories, as Gurmit Ji saw his love for amateur photography from conceptualisation to production. In Kenya, he photographed wildlife, often spending free periods and weekends in the sprawling nature reserves, and the composition of his shots is eulogised by many. “A Nikon man,” Jagdeep Shah calls him, and in many ways, Gurmit Ji’s technical knowledge and flair were before his time. He was, in the words of Nirmal Singh, ‘an early adopter’—“He did something totally different and had immense influence later.”

His quest for the best has infiltrated the ethos of Darbar. Jagdeep Shah, whose father, Kanti Shah, was close friends with Gurmit Ji, grew up listening to the two waxing poetic about the latest equipment—and the potential it held. “We learnt at a very young age that the equipment should be the best we can afford,” says Shah. Today, in an unlikely marriage, Darbar has used 8K cameras, offered surreal, immersive experiences starting with the world's first Hindustani and Carnatic VR360 video and become a trendsetter in deploying cutting-edge technology to adequately represent the centuries-old genre. “We used 4K seven to eight years ago,” explains Shah, who has been a championing volunteer with the organisation since 2015, “And one day, we realised...people were following us.” Like Gurmit Ji’s insistence on flawless photographical composition—”If you take the shot; take it once,” he’d say—Darbar has striven to be at the forefront of bringing live music to the screen with as much fidelity as possible to the real experience. While adapting strategies to cater to how Millennials and Gen Zers consume content—and later, to adhere to travel restrictions imposed by a global pandemic—the end goal has always been, “To get the high clarity. To get the feels and ultimately kindle this desire to go to a live concert,” says Shah. Such commitment to excellence has infiltrated the operations of the Darbar team, as Gurmit Ji

For starters, it wasn’t fame or monetary recompense. Nor was he amassing art to grace the walls of his own home, as he gave most of his paintings and photographs away. “He’d say, ‘Here! Have this!’ and literally take art off the wall to give away,” shares Harmeet. But in that act of suspending a moment for posterity, Gurmit Ji was, in a way, immortalising his roots. At first, it may have stemmed from his sheer passion for everything he did. But in 1978, after Gurmit Ji took the Amrit ceremony of initiation from Sant Baba Puran Singh (1899-1983), his spiritual awakening led to a more single-minded focus on spiritual elevation. “At the end, his life was predominantly spiritual,” shares Sandeep, and many of Gurmit Ji’s activities fed a higher purpose.

In the late 80s and 90s, life for Gurmit Ji became a balancing act of simran (the remembrance of God through recitation of His name), sewa (work or service performed without any thought of reward or personal benefit) and kirtan, three pillars that Sikhs visualise using the analogy of a bird. While sewa and simran constitute the two wings, kirtan is the rudder helping the bird stay airborne. And balancing the three is an act requiring dexterous spiritual control, much like aerodynamics. Gurmit Ji had this control down to an exact science. Once he took the amrit, he staunchly upheld the beliefs, never missing a prayer and refraining from eating meat or cutting his hair till his last breath. During his later years, he measured the drive to different schools across the Leicester-Shire Schools district not in minutes or kilometers—but by calculating how many Chaupai Paath (prayers) he could fit in during the distance. Nirmal Singh recalls an incident, “We’d gone to do sewa in August, 1998 and were visiting a shrine atop a mountain to pay our respects. It must have been over 200 steps, and we were weighed down with camera equipment. Sandeep and I, despite being decades younger than Gurmit Ji, took the car. And at first, Gurmit Ji came with us. But he turned around at the top and descended all the way down, because he wanted to say a prayer with every blessed footstep. The rest of us—we just stood and watched. He was the epitome of devotion and perseverance.” In this manner, Gurmit Ji viewed commonplace activities through the lens of potential worship. In photography, that lens was both metaphorical and literal. “From 1996 to 2004, you see this deluge of religious photography. Gurmit Ji photographed the gurudwara, events, trips and kirtan. When our Sikh community met His Holiness the Pope in 2000, he’s the one who took the pictures. And when we started having more interfaith dialogues, his images were used for that as well...projected on a wall to be cost-efficient at the time,” recalls Singh. And of course, the culmination of his photographic art as sewa was with the Kar Sewa of the Golden Temple (Darbar Sahib) in Amritsar, India. To put this into context, the Golden Temple is, “...the sanctum sanctorum for Sikhs,” explains Sandeep, likening it to the elevated status of Makkah for Muslims. Though many spiritually enlightened individuals toil away without the good fortune to visit—far fewer kirtanias (those who perform kirtan) have the privilege and honor to play within the temple. In 1997, Gurmit Ji accompanied Giani Amolak Singh Ji and Ragi Baldev Singh Ji within the temple. Never one to miss an opportunity to empower others by bringing them to the forefront, a student of his recalls Gurmit Ji asking him to come perform—an overwhelming experience that positively shook the student and astounded him by virtue of Gurmit Ji’s sheer generosity and magnanimity. However, the pinnacle of Gurmit Ji’s commitment to his faith is perhaps best exemplified by his 2005 visit to photograph the Kar Sewa. After photographing the mesmerising process the entire day and navigating amid hordes of worshippers and sewadars, he set his camera down to dredge part of the residue himself. The memory—and the opportunity for sewa—was incredibly dear to his soul, and at the time of his death, he had been excitedly working on the upcoming photography exhibition offering a rare glimpse into this surreal process. “Dad passed away two weeks before the exhibition,” Sandeep explained, “But in his pocketbook, he’d written out all the dimensions. I reverse engineered it and figured it out to posthumously release the photography in an exhibition titled Labour of Love. It’s what he would have wanted.” Art as sewa: Kirtan And if photography was the practice in which he encapsulated streams of sewa and dedication, kirtan was the ocean itself. According to Bhai Sukhbir Ji, “Tabla was his sewa, and kirtan was the first love of his life.” Kirtan, which is devotional singing in Sikhism, is traditionally accompanied by the tabla, and contains scripture written by the gurus themselves. The bani (sacred words) of the Gurus are said to be the revealed words of God, and Sikhs believe that the immutability of these verses is decreed by divinity itself. And when those words are sung and set to raga, kirtan is born, explains Bhai Sukhbir Ji. “The highest mode of worship is when you’re reciting the name of God and doing good deeds,” he said, “And Gurmit Ji was so utterly immersed in this...it was trance-like. I truly believe he had an out-of-body experience when he was absorbed in kirtan.”

For nearly 50 years Gurmit Ji’s accompaniment of kirtan through his prolific tabla became a mainstay at gurudwaras and religious gatherings across the UK, but his prowess predates the London and Leicester years. Even in Kenya, he had been playing at the local gurudwara. In fact, Sandeep would argue that his father’s love for kirtan was not a by-product of kirtan, but the other way around. Kirtan was his destination, and the taal of his tabla was his vehicle. When he asked his father what his favourite music was, Gurmit Ji responded in a single word without missing a beat: “Kirtan.” His wife, Mohinder Ji, relentlessly supported him both in his spiritual and musical endeavours over a sustained period of time, and kirtan brought them closer together. Fostering a stronger sense of communion, the couple attended religious programmes together—with him on the stage and her in the congregation, explains Sandeep. It truly was a way of life. Gurmit Ji’s deeply religious journey, which involved serving spiritual leaders such as Sant Baba Puran Singh (1899-1983), Bhai Sahib Norang Singh (1926-1995) and Bhai Sahib Mohinder Singh Ji Ahluwalia (1939 to present), is steeped in moments of complete spiritual abandon to the principles of sewa and simran, punctuated with the pulsating beats of his lyrical tabla. These moments co-existed in that far off space where humanity reaches its height, and almost otherworldly dignity sets in. Sandeep remembers the juxtaposition of seeing his father enthusiastically serving as a sewadar and bending down to wash the pilgrims’ feet at Anandpur Sahib at the religious festival of Holla Mohalla before taking the stage for his kirtan the following morning—a unique combination of humility and talent encapsulated by the Sikh saying of 'Maan Neeva Maat Uchi'. Translated literally to ‘mind/ego low and morality high’, the approach prescribes discarding one's ego and living a life of humility. And that’s exactly what Gurmit Ji did. He extended his love for kirtan outside of the gurudwara as well, channelising it with his characteristic intelligence. In 1997, when the Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple) in Amritsar required gold gilding and the global sewa outreach initiative came to Birmingham, Gurmit Ji didn’t follow the traditional practice of raising funds by going door-to-door. Instead, he continued an initiative taken by his wife, taking the Guru Granth Sahib (the central religious scripture in Sikhism that is regarded as the eternal guru) and inviting friends and members of the local community to his house for kirtan and langar—effectively steering the collection drive into an event. “In that one move, the whole community joined together in the united cause for sewa,” explains Harmeet. It was so well received that the tradition continued far after the gilding was complete, with different houses hosting the sangat (true spiritual congregation, complete with the Sukhmani Sahib prayer of peace, simran meditation and two to three shabads (hymns) of kirtan) each Saturday. Many viewed it as a spiritual cleansing of their homes and their aura, vying for the honour of hosting the next congregation. And the typical custom of offering daswand, (giving back—ideally at least 10% of one's time and financial contribution) at the feet of the Guru Granth Sahib Ji before entering meant that unfathomable amounts were collected for charity. Gurmit Ji was also offered the privilege and honour of making the last prayer (ardaas) on behalf of thousands of worshippers at the end of a three day Akhand Paath or 11 day Sampat Paath reading of the Guru Granth Sahib Ji, not once, but multiple times—testament to the spiritual leader’s faith in his devotion, explained Bhai Sukhbir Ji. Small surprise, then, that he became a community mentor, serving as a guide for at least 30 families, he explained, and a father figure for many more. Gurmit Ji’s life, it seems, was now irrevocably entrenched on a fast-track to spiritual elevation, soaring in progression. Right until its end. His last meal? Karah Parshad (sacred food served at the close of a worship ceremony) and food from the Sukhmani Sahib Paath langar, notes Sandeep. As Gurmit Ji transitioned from a worldly to a spiritual life, he befittingly went with the consecrated food of his spiritual community. Eternal optimism And yet, his spirit survives. In keeping with the Sikh expression referring to a frame of mind aspiring to maintain a state of eternal positivity and optimism, the spirit of Chardi Kala frames his death not as a loss, but a necessary transition to meet his maker. Because with eternal optimism, death isn’t the end. Death is a comma, not a full stop. It’s simply a horizon marking the limits of our sight. To everyone who knew him, Gurmit Ji lives on. How would he have felt about Darbar today? “Well, he definitely wouldn’t have been happy about seeing his pictures plastered everywhere,” laughs Harmeet, while Sandeep believes that, ever the hard taskmaster, his father would have acknowledged the beauty of the festival with everyone except him. He would have been happy to see artists getting the recognition and platform they deserve, everyone agrees. For Ameeta, the moment when she feels his presence strongest is during the free for all fringe events. “Off the streets of Southbank, the doors are opened and fusion fringe events happen. The whole area is flooded with people, and everyone—regardless of colour, class or religion—flocks to the music. If he was with us today, he would have been proud of the way Darbar is carrying forward his work perpetuating music through his students, but I think those fringe events really embody a lot of what Dad stood for.” Sitting in the Darbar concert hall, Shaminder feels it’s those moments of sheer awe and transcendental bliss, when she can think to herself, “I am in the most beautiful place on this Earth at this very moment. I wish the whole world to feel what I could feel,” that would have resonated with her father most. The legacy he left goes beyond a simple desire to share his passion for tabla, or even for music. It was to make this land his home, for him and for his diaspora. “When we moved to Africa, we were nomads who came with nothing,” says Shah, referring to the roots of Sikh heritage in East Africa, which were initially intertwined with the construction of the British railway line. Like Gurmit Ji and Shah himself, the members of the Sikh community who migrated twice, once from India to East Africa, and then from East Africa to the UK, had, “Never built up anything in the attic,” he explains, “The one thing we held onto was culture and heritage. We essentially hoarded on heritage, and what bound us together was music. Everything gets diluted. English takes over. But the language of music perseveres.” And it has. Today Today, Gurmit Ji is remembered as a musician, teacher, mentor, advocate for the arts and as an inspired artist. For his students, he took the place of a father figure—sometimes even babysitting their infants to facilitate riyaaz. In his spiritual community, he is regarded as a prolific sewadar serving humanity with purity of thought, deed and action. He is cited as an example for embodying the Sikh values of sewa, simran and kirtan, which served as the ‘passport’, if you will, for his spiritual elevation. His status as rhythmic gatekeeper through tabla accompaniment of Giani Amolak Singh Ji embedded soulful kirtan in the social and moral tapestry of the Sikh diaspora in the UK as well as catering to a global audience, and transcended to individuals from richly diverse backgrounds through his peripatetic teaching programme.

Today, Gurmit Ji lives on in many lives—be it the students who still play and teach or the artists from the galis (alleyways) of India who are given a nepotism and favoritism-free, egalitarian platform to thrive through Darbar. With his rich and multi-faceted personality, he has been and will continue to be many things, for many people. But in the words of Harmeet, “To us, he was just dad.” May the biological family of Gurmit Ji always find solace in his memories, and may his larger spiritual and musical fraternity always remember him in the way he would have liked best: through his legacy of Wand ke Shako. We hope this new phase in the Darbar website will accurately reflect his vision and ethos in the same manner we have striven to do justice to his legacy in the past. Because he was, truly, a spectacular man. END On behalf of the entire team at Darbar, the writer would like to thank the following individuals for their generosity of time and sentiment in putting together this piece. Even the deepest of dives can not do justice to the illustrious life of Gurmit Ji, and the current article can only scratch at the surface of the beautiful and heartwarming conversations that were had in the process. In the interest of cohesion and flow, overlapping points have not been attributed in cumbersome notations, but the writer acknowledges that each of the facts cited in this article has been amassed through first-person reportage and interviews with the individuals mentioned below. Thank you, everyone, for your time and for sharing a piece of your story with us.

Friends 1 Malkeet Panesar |

Classical music can uplift your mind, body and spirit—Indians believe it constitutes the ascent to divinity...

Read More

Charlie Parker, the legendary jazz saxophonist, once said: 'Music is your own experience, your own thoughts, your...

Read More

Darbar believe in the power of the Indian classical arts to thrill, stir and inspire a global audience. But what does...

Read More

The beginner's guide to Indian classical music. Whether you’re completely new to raga music or just need a refresher, we’ve put together this brief overview of all things raga music to help you feel at ease when visiting one of our concerts or watch our videos on our YouTube or our Darbar Concert Hall.

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, music and musings across our social channels

For hundreds more clips and shorts, vist our YT page here